What’s the best renewable heating system?

From biomass to solar panels, what’s the greenest, cheapest way to heat a home?

Between them, water and space heating account for almost 80% of the energy used in our homes. So if you’re designing or refitting a home to be as green as possible, adding a renewable heating system is essential. Coupled with insulation and energy-saving measures, such as triple glazing, renewable heating from biomass or a heat pump could slash emissions – it’s likely to lower your running costs, too.

But low-carbon heating is often more expensive to install than simple electric or gas-fired alternatives, and the financial support available is patchy. If you’re going to invest your own money in going carbon-neutral, you’ll want to choose the best technology for your project. Here we look at the major alternatives, compare the support that’s available, and discuss how they might perform.

Low-carbon heating technologies

There’s plenty of innovation in space and water heating, but to be considered renewable, heating products must not burn fossil fuels. Typically that means either running on electricity or burning biomass – non-fossil fuels that absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and which can quickly be re-grown.

There’s active debate about whether the latter is truly better for the environment – or even renewable – but let’s not get bogged down in the details. What’s certainly true is that nobody considers biomass a renewable fuel unless it’s grown sustainably, usually meaning that it’s sourced from existing plant or animal waste. Similarly, electric heating is only as low-carbon as the electricity used to power it.

With these caveats in mind, the major renewable heating technologies are biomass boilers and burners, heat pumps, solar water heating, and electric heating. This last category includes direct panel and water heaters, storage heaters, and infrared panels.

It’s also important to consider microgeneration, such as solar PV or wind. Although these aren’t heating technologies, they can be an important way to provide renewable energy to electrical heating systems.

Electric heating

It might be surprising to learn that all forms of electric heating can be renewable. Even bar fires and panel heaters are carbon-neutral if they’re using electricity from your own solar panels, or if you’re on a 100% renewable tariff. Basic electric space and immersion heaters are essentially 100% efficient, converting every kilowatt hour (kWh) of electricity they use into one kWh of heat. They’re cheap to buy, too.

Electricity is expensive, however, and heating a property and its water uses a huge amount of it. The average four-bedroom home uses around 17,000kWh of energy for heating each year – at the October 2023 price cap of 27p per kWh, that would be an incredible £4,600! In practice, off-peak tariffs bring that price down, but even using off-peak electricity only you could still pay £2,780.

Infrared panel heating provides one alternative. Instead of heating the space, it heats the objects and people within it, a bit like when sunlight keeps you warm on a cold spring day. This typically uses much less power when on, and panels can be switched on and off dynamically as people enter and leave a room, but it’s still a niche choice as a primary heating method.

We’ve used the latest Energy Saving Trust figures for price and carbon dioxide equivalence to calculate typical costs for the main technologies. For direct electric heating, it’s:

Cost per kWh 27.4p, CO2 emissions per kWh 225g

Heat pumps

When it comes to efficiency, nothing beats a heat pump. These are a lot like a fridge that works in reverse, taking heat from the air or ground and ‘pumping’ it into your home. Because they’re largely moving heat rather than generating it, they typically output around 3.5kWh of heat for every 1kWh of electricity they use – specified as a coefficient of performance (CoP) of 3.5. In the example above, that would slash the annual bill to a far more manageable £1,310, and a heat pump can be cheaper than a gas boiler.

Heat pumps are at their most efficient when heating water to lower temperatures than a conventional boiler – around 40-50℃ rather than 55-70℃. For this reason they’re best used with wet underfloor heating, and they may need larger radiators to be effective in other rooms. And because their hot water is less hot, they’re usually partnered with a larger water cylinder that stores more of it.

Heat pumps are an excellent choice for highly insulated buildings, where they can provide near-constant, low levels of heat very efficiently. They’re also ideal alongside microgeneration if you’re aiming for carbon neutrality. For rural properties, a heat pump is cleaner and more efficient than an oil-fired burner. It’s likely to be cheaper to run, too, although older properties will need insulation improvements to get the best from one.

If you’ll be running a heat pump on mains power, it’s essential to choose a carbon-neutral tariff. That said, heat pumps are so efficient that it’s less environmentally damaging to power a heat pump with electricity generated from fossil fuels than it is to burn oil or gas in a boiler.

Cost per kWh 9.8p, CO2 emissions per kWh 80g (air-source)

Cost per kWh 6.7p, CO2 emissions per kWh 55g (ground-source)

Biomass

Biomass comes in a few different forms, from wood and firelogs for traditional fireplaces and log burners, to chips and pellets to burn in biomass stoves and boilers. You can use biomass to heat single rooms or fuel a boiler for an entire central heating system.

We’re probably all familiar with log fires and log burners. While these heat just one room, each can be fitted with a back boiler and plumbed in to provide water heating. Logs can be a cheap fuel source, but only if you order them in bulk – and ideally a year in advance so you can take advantage of cheaper unseasoned wood. That means you’ll need a large, undercover and airy storage place. You’ll minimise the environmental impact of wood burning if you buy from a local, sustainable source.

Biomass burners typically burn chips or pellets, which can be fed automatically from a large hopper. Again, you’ll need a space to store fuel. Biomass boilers themselves are typically a bit bigger than an oil or gas equivalent, so they might not fit in the space vacated by an old boiler.

Biomass heating equipment generally needs more maintenance than other forms. All burners and hoppers need to be manually fuelled and regularly cleared of ash. There may also be health risks from particulates that escape open fires, and log burners when the door’s open. On some still days, log burning can create localised build-ups of pollutants, including particulates and nitrogen oxides.

In its 2023 Environmental Improvement Plan, the government was clear that it wasn’t considering a ban on domestic burning. However, it introduced a new limit of 3g of smoke per hour for stoves installed in Smoke Control Areas. You can find out from your local council whether you live in one.

Cost per kWh 13.8p, CO2 emissions per kWh 48g

Solar power

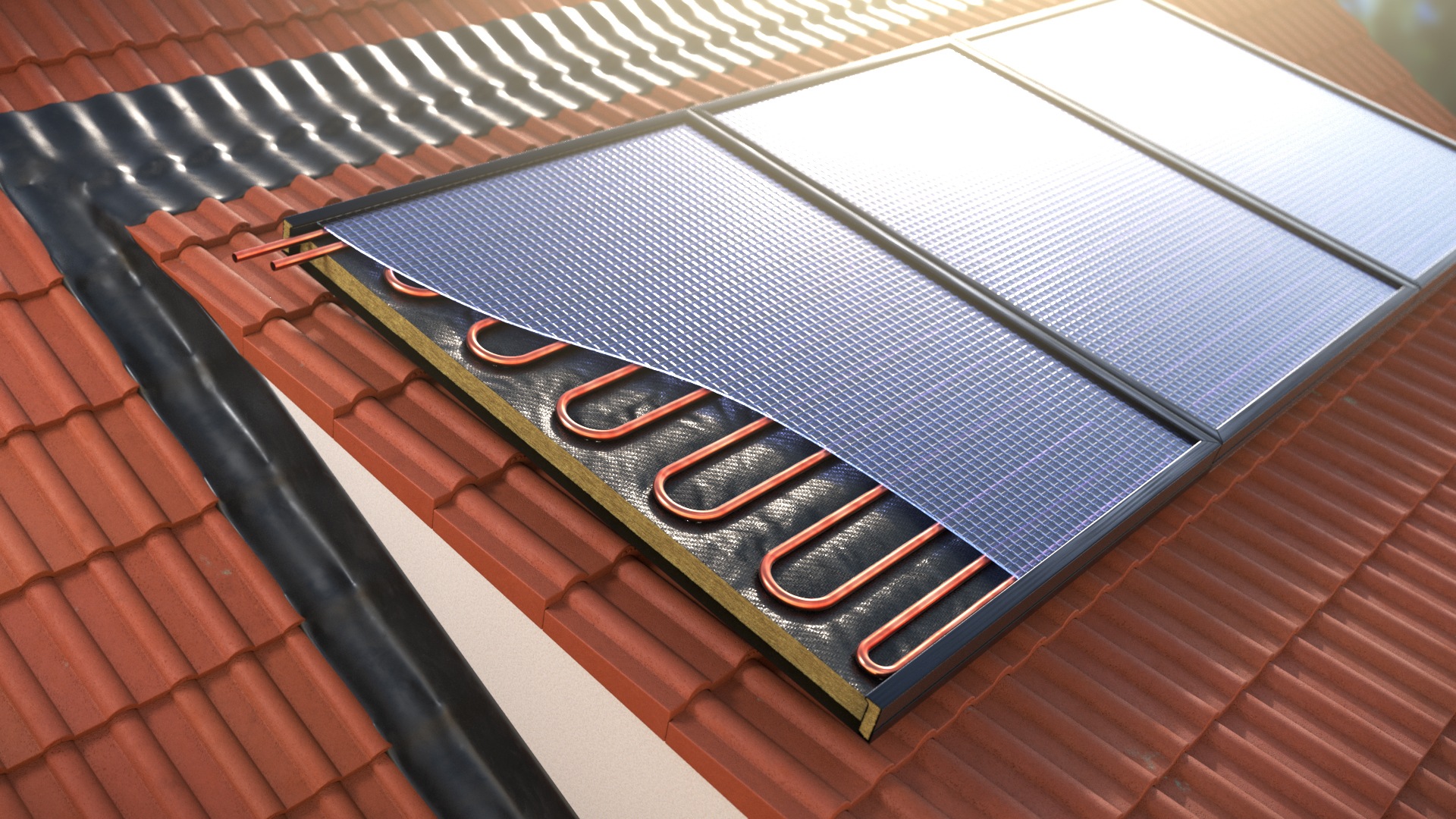

As we mentioned, photovoltaic (PV) solar panels aren’t a heating technology, but their electricity can be used to power electric heaters or a heat pump. Alternatively – or additionally – you could choose to install solar water heating. Because this uses heat from the sun, rather than first converting it to electricity, it’s more efficient than using solar PV to power an immersion heater. It typically reaches around 60% efficiency versus the 24% or so you’ll get from the best solar panel/immersion heater combination.

Using solar electricity to power a heat pump could be slightly more efficient, depending on the heat pump’s CoP. If you have solar panels working at 24% efficiency, powering a heat pump with a CoP of 3.5, the system could exceed 80% efficiency overall (3.5 x 0.24).

Heat pumps and PV panels are affected by temperature: solar panel efficiency can drop by as much as a quarter in high summer temperatures, while the CoP of an air-source heat pump falls in cold weather, so their combined real-world efficiency may be lower. However, a heat pump has the advantage that you can still power it from mains electricity or a home battery system when the sun isn’t shining. With solar water heating, you’ll need a backup heat source.