The timber cottage renovation in Cornwall

These self-builders created a healthy house using the principles of breathable construction

Sometimes, the solution to your problems can be right under your nose – you just haven’t noticed it. This is exactly what happened to Gregory Kewish and Rebecca Sturrock with their Grand Designs timber cottage project in Cornwall.

They were struggling to sell their house in Padstow, which they had recently renovated, and were renting a small cottage at Rebecca’s parents’ property while looking for their next project.

‘One evening, we decided to go up on to the roof to look at the view, and we realised the full potential of the cottage and the site,’ says Gregory. ‘Rebecca grew up at this property, but had never seen the view before. That’s how we got the idea to build here. We then started to look at the numbers, to see what we could afford.’

Gregory, who has a Masters degree in architecture from the USA, put together a design brief for the timber cottage in Cornwall. ‘We wanted to give ourselves more room and provide our twin daughters with their own bedroom,’ he explains. ‘The existing cottage only measured 42 square metres, so we needed extra space.’

Gregory, here with Rebecca and twins Billie and Ava, built all the furniture himself, including the dining table and benches. Photo: Paul Ryan-Goff

‘We decided that we could do something quite nice for a reasonable amount of money, and both of us are interested in novel building techniques,’ Gregory continues. Having worked with cross-laminated timber (CLT) on projects in Jersey he realised that, due to the structural principles of the material, he could cantilever a new house over the old building quite cheaply in order to provide his family with a much-needed bigger floor plan.

‘I have asthma, so I wanted to create a healthy house using the principles of breathable construction, to which CLT is perfectly suited,’ he says.

The couple were also keen on retaining part of the existing cottage. ‘We wanted to keep one of the stone walls that formed the gable of the old pigsty,’ says Gregory. ‘We thought it would help to root the building in its place, while also offering a great opportunity to express the differences between the precision of the German-engineered timber panels and the existing, rustic wall of the original pigsty.’

All kitchen and utility appliances are A++ rated. Photo: Paul Ryan-Goff

They were captivated by the old construction techniques that they found when they stripped back the property. ‘It was a farm building that had been added to over the years in a very incidental way,’ says Gregory. ‘The pigsty had been thrown together using an assortment of materials that the farmers had at the time. It was this quality that we liked – that someone just built something from whatever they had lying around on the farm.’

It took just under a year for the couple’s proposal to obtain planning consent. ‘Our first submission wasn’t well received,’ Gregory explains. ‘Cornwall council loved our design, but the local parish council wanted us to put a pitched roof on the house, which increased our costs by about 15%.’ Although alterations had to be made, Gregory recognises that the Localism Act was instrumental in gaining consent for a larger structure.

‘It allowed us to build something in the countryside that would most likely have been contrary to planning policy,’ he says. ‘It’s an interesting development that local communities can have a lot more control in terms of deciding what they do and don’t want in their area.’

Photo: Paul Ryan-Goff

With permission granted, Gregory set about looking for a CLT manufacturer and an experienced CLT engineer. Usually, cross-laminated timber in the UK is supplied by specialist companies that provide design, engineering and construction services, but Gregory was keen to source the materials and build the house himself to cut down on costs and gain experience. He found Teckniker, an award-winning engineering firm based in London, which he worked with to achieve the structure.

He then contacted a small independent manufacturer in Germany, Eugen Decker, which agreed to supply the CLT. ‘They said no at first because they didn’t sell to individuals,’ Gregory explains, ‘but I kept returning to discuss ways forward, and eventually they agreed.’

For a small fee, the manufacturer took the engineering and Gregory’s CAD drawings and used them to cut the timber to size and specification, and in October 2013 – after the pigsty had been knocked down – building work finally commenced. Initially, Gregory went back to the UK specialists in CLT to see whether they would build his house and also include him on the team, but they wouldn’t allow a novice to work with them. So he decided to build the house himself with the help of a family friend, builder Richard Mashiter.

Photo: Paul Ryan-Goff

‘I soon realised that I wasn’t very fast at the blockwork, and the CLT was due to be delivered, so Richard came to help me,’ he says. ‘He ended up staying on for at least three quarters of the project.’

Aside from the horrendous winter weather and a small accident – when Gregory nearly lost a finger – they were able to keep close to the original schedule, only falling behind by two months. Nine months after work began, Gregory and his family were able to move into their new home, and it’s easy to see why Gregory was so intent on using cross-laminated timber. The end result is a warm-looking, spacious interior full of natural light, which Kevin McCloud described as ‘one of the most beautifully crafted houses I’ve ever seen’.

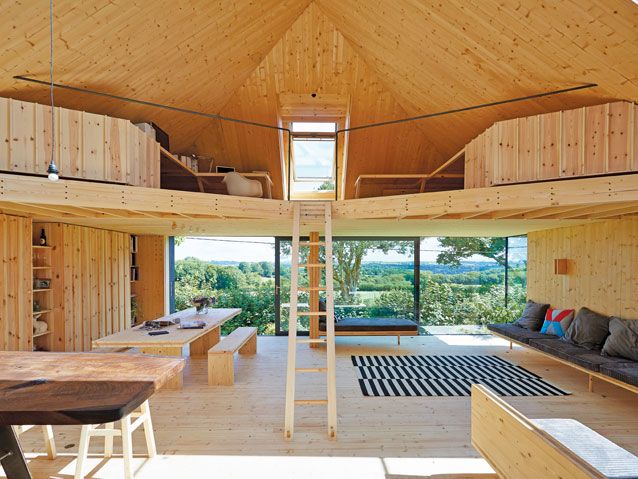

As you walk through the front door, the back pantry kitchen is on the left and a boot room and WC are on the right. Another metre and a half ahead, steps on the right lead down to the old pigsty, which now houses the two bedrooms, an en-suite shower room and the main family bathroom. At this point the hallway then opens up into a massive seven-metre by six-and-a-half-metre space, complete with a panoramic window that provides the uninterrupted scenic view Gregory and Rebecca were so keen to capture.

Photo: Paul Ryan-Goff

In the centre of the open-plan area is a robust ladder, which takes you up to an office space under the gable roof. Gregory even built all the furniture himself, including the dining table and benches, the seating area that stretches from the wood burner to the picture window, and the cantilevered oak worktop in the kitchen.

‘We decided to keep the cross-laminated timber exposed for the floor,’ says Gregory. ‘Because it’s such a high grade of timber, it didn’t seem right to cover it in another wood, for an extra cost.’ He’s also a fan of the markings that the build process has added to the timber. ‘We like the fact that there are incidental marks in the floors and on the walls from the construction process. The house already has a story; it has the charm of a hundred-year-old property.’

When asked what his favourite part of the project is, Gregory isn’t able to pinpoint just one thing. ‘Our favourite space is pretty much everywhere we stand,’ he says. ‘Every bit of the house provides us with something interesting or beautiful. We wanted to create a modest-yet-ambitious property that would inspire all of us every morning, and we think we have achieved that. We love it’.