Rainwater harvesting: the pros and cons

Collecting rainwater to use in your home can be a sustainable way to reduce your water consumption, but the figures don't always add up. We explain why...

Collecting rainwater sounds like a great way to reduce your mains water use, especially at those wet times of the year when it feels like it’s been raining forever. In fact, depending on your property, its location, and the amount of water you typically use, you could reduce your mains water consumption by almost half by installing a rainwater-harvesting system. This sounds like a no-brainer – but the financial and carbon calculations don’t necessarily add up. We take a closer look at the pros and cons of collecting rainwater to use in the home.

What is rainwater harvesting?

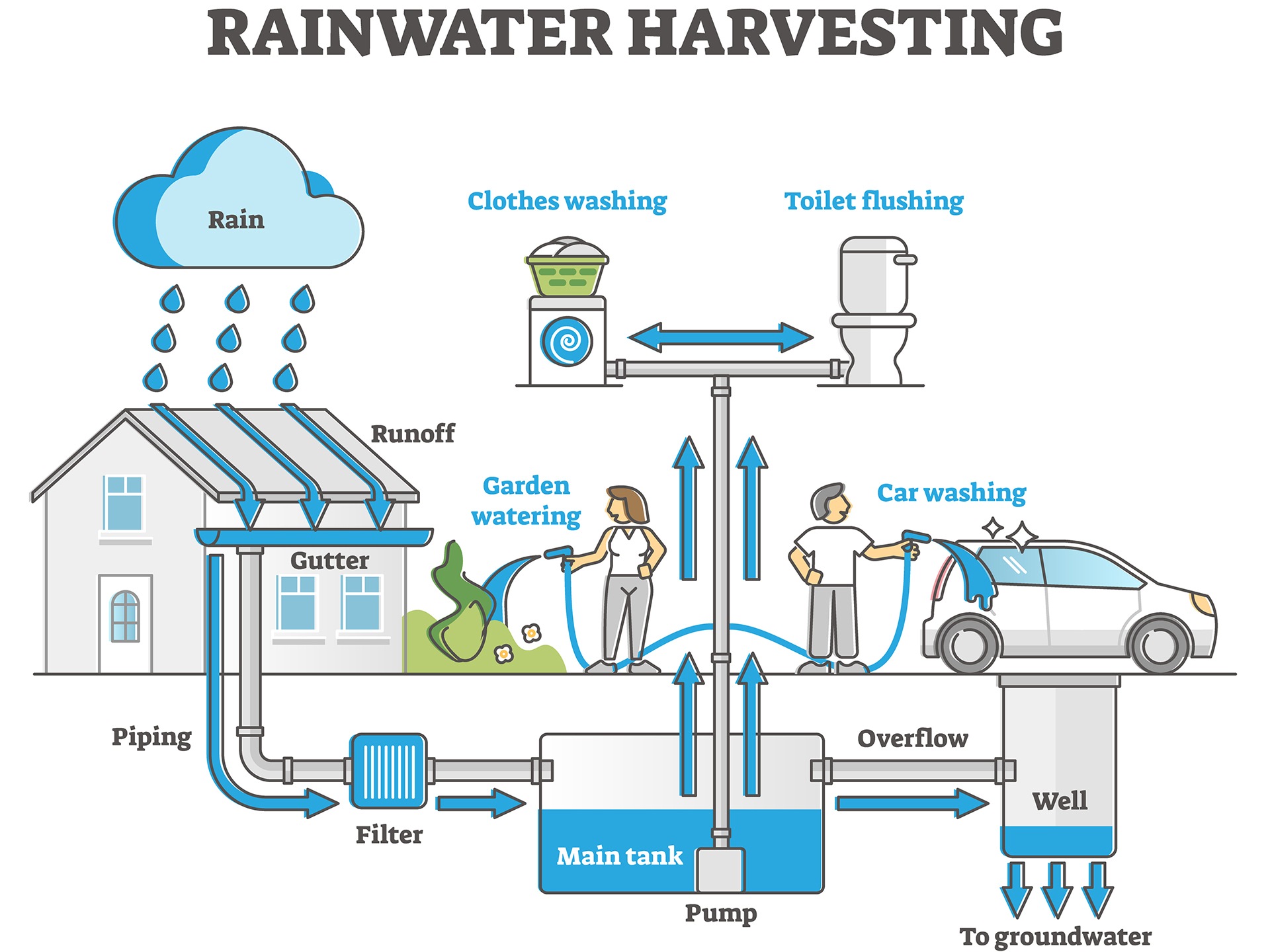

Rainwater harvesting simply means collecting rainwater to use. In the past, many people collected rainwater from their roof in a rainwater butt to use to water their garden, and this remains a great idea. But today, more ambitious set-ups allow you to use rainwater to flush your toilets and run your washing machine.

- Image credit: Adobe stock

Potable vs non-potable water

Collected rainwater is classified as non-potable, which means it isn’t suitable for drinking, cooking, or personal bathing. But, as we said, it can be used to flush loos and in washing machines. Rainwater can be treated to make it drinkable, typically using UV filtration. But this is an expensive business and probably only likely to be worthwhile in an off-grid setting where there is no mains supply.

Rainwater vs greywater

Greywater is waste water from washing and bathing. This can be recycled for flushing toilets and some uses in the garden, and the companies that sell rainwater harvesting kits often sell greywater-recycling gear, too. But greywater is more complicated to deal with than rainwater because it contains small amounts of pathogens and soap and detergent residues, which means it can’t be stored for long,

How is the water collected?

The best way to collect rainwater is from a sloping roof via a downpipe into a tank that’s either above or below ground. A filter is needed to stop leaves, twigs and other debris getting into the water tank. The tanks are not the most attractive of things, though you can, of course, shield them with fencing or plants. However, most professional domestic systems use underground tanks. If you haven’t much outdoor space, there are purpose-made tanks that will sit under your driveway.

The size of the tank required for a domestic set-up will likely be between 1000 and 6000 litres. The amount of water you’ll collect in a year – the rainwater yield – is calculated roughly as follows: area of roof (m2) x annual rainfall (mm) x run-off coefficient of roof (about 0.75 for a tiled pitched roof). Meanwhile, average water use per person is about 150 litres a day.

- Image credit: Adobe stock

What is a typical system?

There are two main types of systems used to distribute the water to the toilets and washing machine: gravity and direct (or pressurised) systems. (Or a combination of the two).

In a gravity system, the rainwater is pumped from the main tank up to a small header tank in the loft, from where it is available when needed to flush toilets or run the washing machine. A newer type of gravity-fed system channels water from the roof directly to a large tank in the loft rather than sending it to an underground tank first. In a direct system, on the other hand, the water is pumped directly from the main tank to the toilets and washing machine.

The systems can be topped up automatically from the mains if the water falls below a certain level. You’ll need to clean the filter every couple of months and do some routine maintenance on the system every so often.

Special features you can look out for include holiday mode, which empties the header tank every few days if you’re away to prevent water going stagnant, or mains-only mode, which allows all the rainwater to be diverted for use in the garden in case of a hosepipe ban. You’ll probably also want to have an outdoor tap as part of your set-up.

Rules and regs

British Standard BS EN 16941-1: 2018 covers rainwater harvesting systems, setting out standards to ensure systems are safe, watertight, and designed to avoid problems, such as stagnation and the growth of problematic bacteria. Systems will also need to meet building regs, which cover things like how far tanks are placed from building foundations, and the use of ‘Not drinking water’ signs.

Some manufacturers get their products approved by WRAS, the Water Regulations Approval Scheme, an independent body that certifies that products are safe for use in the water system.

Suppliers

The trade body for companies that install rainwater harvesting systems is called the UK Rainwater Management Association. You can find a list of their members on their website. And you will find lots more information about how rainwater harvesting works as well as lots of examples of kit on the sites of these specialist companies.

Environmental impact

Although rainwater harvesting has been promoted by the government at various points, for example, as part of its Code for Sustainable Homes, the figures haven’t always added up in terms of sustainability, because of the energy and carbon used to make the pumps, tanks, pipes etc required for a domestic rainwater system. This Environment Agency report on the Energy and Carbon Implications of Rainwater Harvesting and Greywater Recycling set out the problems.

The industry has made lots of progress in recent years to improve sustainability, though, through developments such as low-energy pumps and tanks made from recycled plastic. And more recent research, such as that done by Ricardo for WaterWise in 2020 is more positive about the lifecycle carbon assessment of rainwater harvesting vs mains water. Plus they point out the benefits to wider society of rainwater harvesting in terms of reduced demand on water infrastructure, CO2 savings and flood damage reduction.

If you are going to install a rainwater-harvesting system, to minimise its environmental impact, Judith Thornton, author of Choosing Ecological Water Treatment, recommends choosing a tank that doesn’t need concrete backfilling when it is installed. She also points out that, if your property is off grid, a composting toilet might be a more sustainable solution than a conventional toilet fed with rainwater.

Does it add up financially?

- Image credit: Pexels/Alaur Rahman

Financially, installing a rainwater-harvesting system is more likely to pay off if you’re putting it in a new build with a water meter; and less likely to add up if you’re retrofitting to a home without a water meter.

(As a reminder, you can ask your water company to install a water meter for free in England and Wales. And the Money Saving Expert rule of thumb on whether a water meter will generally save you money is this: if you have more bedrooms than people in your family, or the same number, check out a meter. You can put your details into this Consumer Water Council calculator to work out if a meter will save you money regardless of any rainwater-harvesting plans.)

Retrofit a rainwater-harvesting kit and you could cut your water bills by nearly half if you have a water meter, but the upfront costs are significant: £3000 to £15000. You will need to get a quote for your home from a specialist company, as prices vary greatly according to the type of property, tank, and system.

The Ricardo report says that “smaller installations are not privately beneficial for the installer [homeowner] and are therefore unlikely to see large scale uptake until they become so, either through falling prices or government-backed schemes and interventions”.

On the other hand, the figures might well add up for large commercial developments: a project with a large roof that can use a large volume of non-potable water is the most likely to benefit. Think: the Velodrome in the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park, London, which was designed to incorporate rainwater harvesting.

Part of the reason domestic rainwater systems don’t always add up either financially or in terms of sustainability is because mains water is relatively cheap – and doesn’t have a huge carbon footprint. Ofwat estimates the water industry is responsible for approximately 1% of the country’s greenhouse gas emissions, and the industry is working hard to decarbonise. Meanwhile, the average UK water bill for 2023/24 is £37 a month, though bills vary from company to company. Generally, we are lucky to be able to get cheap, reliable water supplies at the turn of a tap.

Climate concerns

It isn’t entirely clear whether climate change is likely to increase or decrease rainfall in the UK. There has been concern over water supply security in the South East of England in particular. And rainwater harvesting at a large scale could, of course, reduce demand – with the obvious proviso that water is scarcest in areas with the lowest rainfall. In urban areas, harvesting rainwater might help mitigate flooding – and related pollution – during storms, too. However, achieving this would require the technology to be adopted by large numbers of people.

Rainwater butts

So, there’s a lot to consider. If you think it is something you might want to investigate, talk to some specialist companies, get some quotes and do the maths. In the meantime, even if a more complex system for use inside your home doesn’t add up, harvesting rainwater to use in the garden is a cheap and easy idea that almost anyone can benefit from. Plants prefer rainwater to tap water, and you could use it to wash your car or bike too.

- Image credit: Adobe stock

Water butts are available in all shapes and sizes. Get one with a downpipe-diverter kit that will send rainwater into your butt until it threatens to overflow, at which point it diverts it back into the downpipe. The rainwater-harvesting companies also sell larger tanks for gardens that are great if you have a large outdoor space. Rainwater systems are exempt from hosepipe bans if they don’t have a mains backup.