MVHR vs PIV – which is the best ventilation system for your home?

We’re all more aware these days of the importance of ventilating our homes properly. But the choices can be confusing. Here’s our guide to the options

As we insulate our houses more effectively and make them more airtight – to save energy – issues with air quality and condensation can arise. Houses without enough ventilation are stuffy and prone to condensation, damp and mould. But there are now new and efficient mechanical means to ventilate buildings. Here’s how to ensure your home is well ventilated whether its new build or an older property.

Air quality

It’s worth investing in a carbon dioxide monitor to check CO2 levels – and humidity – in your home. A constant supply of fresh air is needed to replace the stale, humid air we generate by breathing, washing, cooking, drying clothes and generally living our lives. Reducing moisture in our indoor air is very important because excess humidity encourages condensation, mould and dust mites.

The best ventilation choices are different depending on whether you are retrofitting ventilation to an existing property or installing in a new build. We’re going to look at new build first.

New build

Minimum standards for throughput of fresh air are set out in Part F of building regulations. The latest version states fresh air should be replacing internal air at a rate of 0.3 litres/second/m2 internal floor area. That means about half an air change per hour.

Building regs don’t prescribe mechanical whole-house ventilation systems for new properties. They allow for natural ventilation, using trickle vents in the windows in ‘dry’ rooms to allow air in, and extractor fans in bathrooms, kitchen and other ‘wet’ rooms to expel damp, stale air. Of course, the problem with trickle vents is that people tend to leave them closed because they can be noisy and, well, draughty. There are, however, new smart air inlets, such as the ones made by Aereco, for both windows and walls, and open and close automatically according to the level of humidity in the house.

Extractor fans

When it comes to extractor fans there are lots of choices: intermittent (on demand: operated by sensor or switch) or dMEV (decentralised mechanical extractor ventilation) fans (low-power fans that run all the time); and axial, centrifugal and mixed flow models. The best choice will depend on the specifics of each room. But they will all be expelling air you have paid to heat.

Natural ventilation is what we have historically relied on to ventilate older properties, but, if you’re starting from scratch in a new building, it would seem sensible to adopt a more sophisticated, modern mechanical approach.

MEV

One option being built into some new properties is centralised mechanical extract ventilation (MEV). This is a kind of halfway house. It involves a central fan unit, often in the loft, connected via ducts to vents in the ‘wet’ rooms in the house. The low-energy fan runs continuously sucking damp air out of the kitchen and bathrooms and pushing it out of the house through a single exhaust vent. Fresh air enters the house through the trickle vents and gaps in the fabric. Sophisticated versions are controlled by humidistats – sensors that detect the amount of moisture and CO2 in the air. These systems circulate air, and the fan should be quieter than a normal extractor fan because it is in the loft or plant room, but, again, heated air is being vented out of the building.

This is why many people see mechanical ventilation and heat recovery (MVHR) as a superior system for new homes. And, if you are building a new home from scratch and specifying it yourself, it would seem odd not to choose the superior system, though it is considerably more expensive.

Passive stack ventilation

Before we look at MVHR, let’s briefly consider one more option for new builds: passive stack ventilation. This is a non-mechanical option where air inlet is again by means of trickle vents in the ‘dry’ rooms and gaps in the fabric. This time ducts run from vents in the wet rooms (kitchen, bathrooms etc) up to vented ridge tiles on the roof, and air pressure does the hard work, drawing damp air up and out of the house. This system needs to be designed and built into the home. It costs less than MVHR. But, once more, heat is being lost all the time.

MVHR

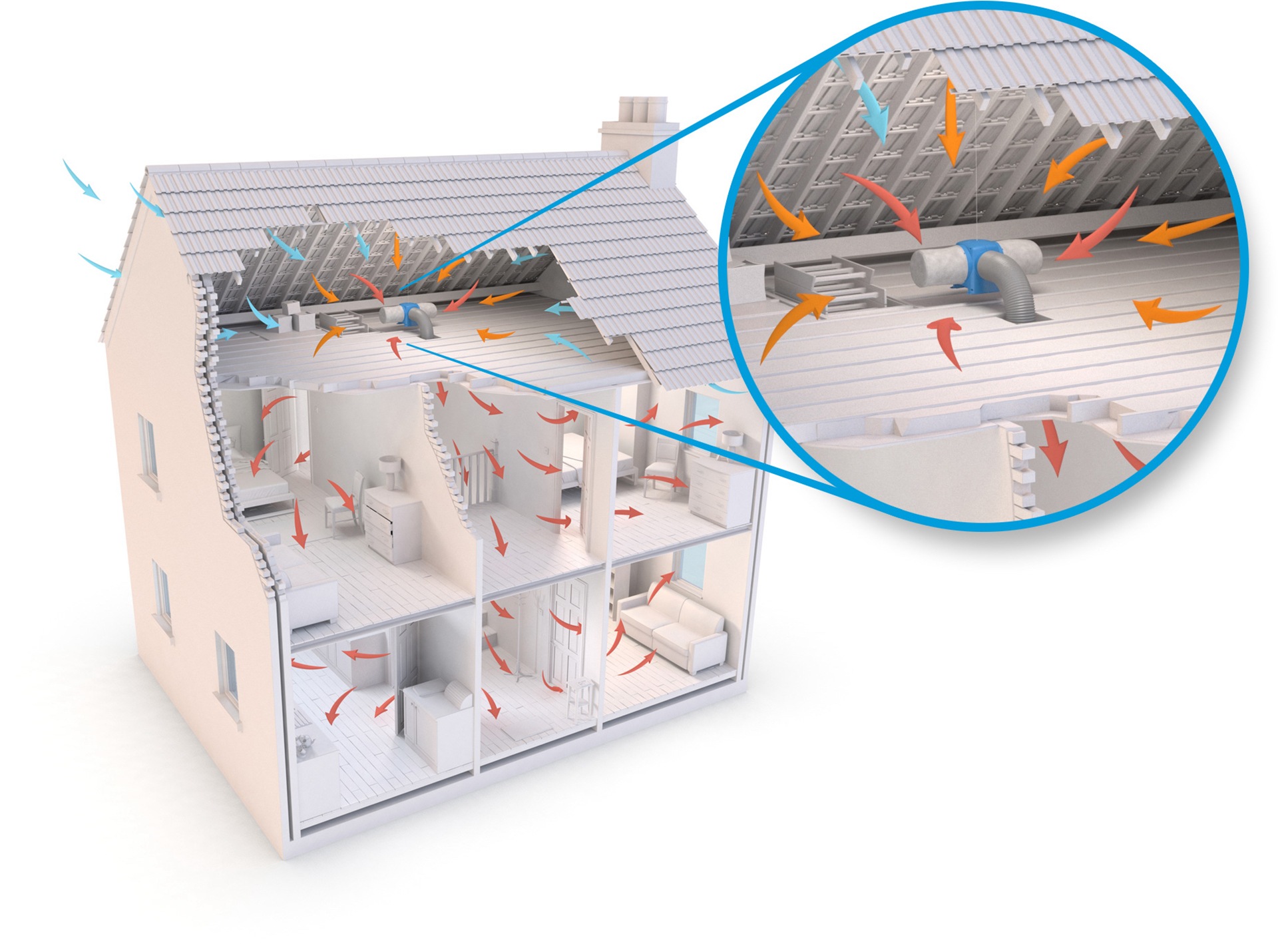

Image credit: Nuaire

If you are designing a new house nowadays, the top-of-the range ventilation option is a mechanical ventilation with heat recovery (MVHR) system designed and built into the fabric of the house from the off. MHVR consists of a fan and heat exchanger unit – often sited in the loft – plus an extensive network of ducts leading to vents in each room in the house. Stale, damp air is drawn out of the ‘wet’ rooms, like bathrooms and kitchen, and into the unit where the heat is extracted from it in the heat exchanger. This heat is used to warm fresh, filtered air that is simultaneously being drawn into the house through a vent in the roof. This warmed fresh air is then pumped down into the ‘dry’ rooms of the house such as the living room and bedrooms. Meanwhile, the now cool, damp stale air is let out through a separate exhaust outlet in the roof. Air circulates around the house in this manner.

MVHR allows you to reclaim about 90% of the heat from the stale air before it is expelled, thus saving money and energy in the long term. But the upfront cost is significant and the set-up should be designed by a qualified engineer as early as possible in the build so the system can be integrated seamlessly into the fabric of the building, not shoehorned in as an afterthought. It’s important to choose the right size unit, or you could end up with a system that has to work too hard to move the air and is, therefore, noisy. The length of the ducting and number of bends in it need be minimised. For best results choose aluminium ducting (rather than plastic) fitted with silencers to stop noise from the fans travelling through the ducts.

Image credit: Nuaire

Filters

The removal of pollen from the air with MVHR can be a real boon for allergy sufferers. Depending on the filters you choose, they will also deal with volatile organic compounds, particulates from cooking, dust, radon, and other pollution. You will need to change the filters every three to six months, depending on how dirty the air is. Although MVHR systems are most commonly installed in the loft, if space allows for a separate plant room, putting the main unit there will make filter changes and routine maintenance easier.

Airtightness

In order for MVHR to work, a building needs to be reasonably airtight, though Passivhaus Trust research has shown that MVHR can work in even quite draughty houses of up to 9m3.hr/m2 @50Pa. In an airtight house with MVHR there are some things you have to do a little differently. For example, open fires are out because they require a chimney, which is not compatible with airtightness. You can have a woodburner, but only if it has its own direct external air supply, sealed off from the room, and excellent door seals. And you may find the room containing the stove gets too hot.

Smart systems

The MVHR fan will usually have different speed settings; for example, you can turn it down if you go away, or turn it up to a ‘high occupancy’ setting if you have a party. And you should be able to bypass the heat exchanger in the summer to stop the house from getting too hot. Some manufacturers, such as Nuaire, also make cooling units that can be attached to MVHR units to cool the home in summer.

Image credit: Nuaire

MVHR costs

The cost of an MVHR system could be anywhere between £3,000 and £10,000 depending on the complexity of the install and the size and spec of the system. Then there are the ongoing costs. The system runs on a small amount of electricity all the time, and you need to pay for filters. And all of this needs to be balanced against the cost of all the lost heat in other ventilation systems.

Retrofitting

Image credit: Florencia Lewis (CC 2.0)

The ventilation choices that are best in new build don’t necessarily work well in old houses. Often there just isn’t the space in older homes for the ducting required for MVHR systems. (It just might be possible to design it in if you are stripping an existing building right back to its bare bones.) Instead, there are some compromise options you can adopt to improve the ventilation of older properties. One of these is positive input ventilation (PIV).

What is PIV?

A PIV unit is an air pump usually installed in the loft with a vent going down into the house. It filters fresh air that it draws into the house through the loft space before pumping it out through a diffuser into the house. As the PIV pushes fresh air into the house, the stale air in the property gets gently pushed out through gaps in the fabric of the building, trickle vents etc.

Image credit: Nuaire

The unit, which is basically a fan with two intakes covered in sock filters, can be hung in the loft or floor mounted. The hanging solution is probably better as that prevents vibrations from the fan being transmitted through the ceiling. The vent from the unit runs down to the ceiling-mounted diffuser. Again, this is a system that pushes heated air out of the house, which is less than ideal in terms of energy use. But PIV systems are good at dealing with condensation.

Image credit: Nuaire

PIV with heater

The air coming into your house from the PIV unit can feel cold in the winter. The way around this is to have a PIV with a heater attached. But even then, the air may still feel cool. And, in any case, the way PIVs are designed to work is by pushing heated air out of gaps in the building fabric. So it is likely there will be some increase in heating costs. This will significantly increase the cost of running your PIV but the heater will only need to be turned on in the coldest part of the winter.

dMVHR

Another option for existing properties is decentralised mechanical ventilation heat recovery (dMVHR). These are single-room MVHR units, such as these made by Vent Axia, which remove the need for all the ducting, so could be a retrofit option. There’s a really interesting piece detailing one family’s largely positive experience with a single MVHR unit installed in their bathroom over a number of years.

Dehumidifier with heat recovery

Another possible option that avoids the heat-loss problem is a dehumidifier with heat recovery (dhr) like the one made by ebac.

Conclusion

So, in summary, the current consensus is that MVHR is the best practice for new builds and PIV can be a good option for older properties plagued by condensation.

That’s the theory. But the solution for each property will be individual. These are still relatively new technologies and smarter solutions are being developed all the time. Information is key: talk to engineers and installers to get a range of quotes and possible solutions for your building.