Complete guide to building foundations

Our guide to groundworks explains everything you need to know about building foundations.

Getting your building’s foundations right is key to getting your build off to a good start and preventing costly problems down the line. Here’s how to get off on the right footings.

What are foundations?

The foundations of a building are those parts beneath the surface of the ground that support the rest of the structure. They have several vital jobs to do, including distributing the weight of the building over a wide area, making sure the building is securely anchored to the ground, and providing a level surface.

Getting the foundations right for a build is vital: problems with the foundations can result in serious structural issues in the finished building that will cost a lot more to fix than getting the foundations right in the first place.

Image credit: Henry Burrows under CC

Footings or foundations

The terms ‘footings’ and ‘foundations’ are often used interchangeably. And ‘footings’ itself is a word with more than one usage, which can be confusing. Footings is used by some people as a synonym for all shallow foundations, by others as a term for the brickwork built on concrete foundations (up to damp-proof course level). To avoid confusion, we will stick with ‘foundations’.

Shallow foundations

As you will be aware if you have ever extended an old house, say, or needed to underpin a barn, buildings in the past were erected with much shallower foundations than we use today.

Today, to head off structural problems, foundations are laid deep, and there are different styles of foundation to suit different types of buildings and plots. What’s best for each building depends on many factors, including the height and type of the building, the type of ground, the water table, available space, nearby trees and the positions of drains.

Image credit: Adobe Stock

Shallow or deep

There are two basic types of foundation: shallow (anything up to 3m deep, but usually much shallower) and deep. Most residential builds on decent ground are fine with shallow foundations, of which there are several kinds, including: strip, trench-fill, pad and raft foundations, each of which has its pros, cons and specific purpose.

Strip foundations

Strip foundations are the cheapest and most common. In the method, each strip foundation supports a load-bearing wall (or row of columns). Trenches for the strips are dug out by digger to match the plan of the building’s load-bearing walls, then a relatively shallow slab of concrete is poured into the bottom of each trench. Finally brick or blockwork footings (often in the form of a cavity wall) are built on this up through the trench to ground level. This option is cheap on ready-mix, but heavy on labour. Wider strip foundations will offer greater strength in ground that is unstable.

Trench-fill foundations

With trench-fill foundations, a trench is dug out, using a digger, for each load-bearing wall. This time, the trenches are filled almost to the top with concrete, then brick footings just a few courses deep are built on top of this. This is a quick choice, and better for clay soils. But you will have to pay for a lot more concrete.

Image credit: Adobe Stock

Raft foundation

A raft foundation is a large slab of reinforced concrete covering the entire area of the building, acting as both foundations for the walls, and as the floors of the building. It can be a good option on some types of unstable ground, such as peat, because it spreads the load of the building over a large area and prevents differential movement of parts of the structure.

Pad foundations

Pad foundations, also known as individual or spread footings, are small round or square concrete foundations that support individual columns or other localised loads.

Reinforcement

Concrete foundations can be given extra strength if need be, with reinforcement with steel mesh or rebar.

Image credit: Adobe Stock

Types of soil

Different types of soil – clay, silt, sand, gravel, chalk, peat etc – have different physical properties that affect their load-bearing qualities, and, hence, dictate what type of groundworks will be required.

For example, the top layers of clay soil (1.2m or so) expand and contract significantly as it gets wet and dries out. To use the technical jargon, clay has ‘high volume change potential’. This means foundations on firm clay need to be dug down beyond that point. The foundation trenches in clay may also be lined with clayboard, a cardboard or polystrene ‘spacer’ that is either compressible or degrades to leave an expansion void around the foundations, protecting the concrete from any expansion in the clay surrounding it. If the clay is soft rather than firm, something more radical might be needed.

Chalk, meanwhile, is problematic because it can crack if it freezes while waterlogged. Peat, silt and soft clay are usually just not sound enough for standard foundations to be sufficient.

Other problems

Other potential sources of problems on a plot include wells, bogs, water courses, archaeological remains, mine workings, old rubbish tips, etc, any of which are likely to require non-standard foundations.

To know what kind of soil you are dealing with and, therefore, what foundations you will need, you will probably need to commission a survey of your land.

To solve the problems, on some sites, you might get away with just digging deeper trenches for your foundations to get down to solid strata. In other situations, you will need to consult a structural engineer who will develop a proposal for engineered foundations custom-designed for the building, site and soil conditions.

Trees

Although trees on a plot are an asset in terms of looks and biodiversity, tree roots can spread a long way, and suck water from an even larger area, potentially causing groundwork issues. Mature trees on clay soil can be particularly problematic.

There are significant differences in the amount of water different tree species require, though: some species, like elm, oak, poplar, willow, hawthorn and cypress, are particularly ‘thirsty’, and can therefore cause potential problems even quite a distance from the building. The National House Building Council has charts giving recommended depths for foundations according to distance from tree, tree height and soil type.

Image credit: Pexels/Marek Piwnicki

Sloping sites

Mark Brinkley, author of seminal self-builder’s guide The Housebuilder’s Bible, has an eponymous rule for the additional costs associated with building on a slope: Brinkley’s Slope Law states that the minimum additional costs associated with building your project on a slope will be £2500 for each additional degree of slope.

If there is anything problematic about your site or anything out of the ordinary about your building, chances are, you will need to get a structural engineer to design and prove the foundations for you. On a tricky site, the engineer might recommend some form of deep foundations, often piles.

Deep foundations

Deep foundations are needed for very tall buildings or when surface soil won’t support a building, and its weight needs to be transferred down to load-bearing subsoil or bedrock. Types of deep foundations include: piles, piers and caissons.

Piles

Piles are the deep-foundation solution you’re most likely to encounter on a self-build project. These are long thin columns of concrete, steel or even timber, made off site and driven into the ground using some kind of pile driver. Or concrete piles can be bored and poured in situ.

Piles can be driven deep into the ground and have a high structural strength. Because they are driven into the ground they don’t generate lots of spoil. Piles are generally cost effective vs digging trench foundations deeper than about 2m deep.

For a residential property, you might perhaps install a row of concrete piles every 2.5m or so beneath the line of each load-bearing wall. The piles would be driven down to solid ground, then their holes filled in with more concrete. Finally a concrete ‘ground beam’ would be poured across the top of the piles, joining them together. And brickwork from there on upwards would just the same as if it were sitting on shallow foundations. RapidRoot are concrete-free piles that work well on sites with lots of tree roots.

Image credit: Adobe Stock

Screw piles

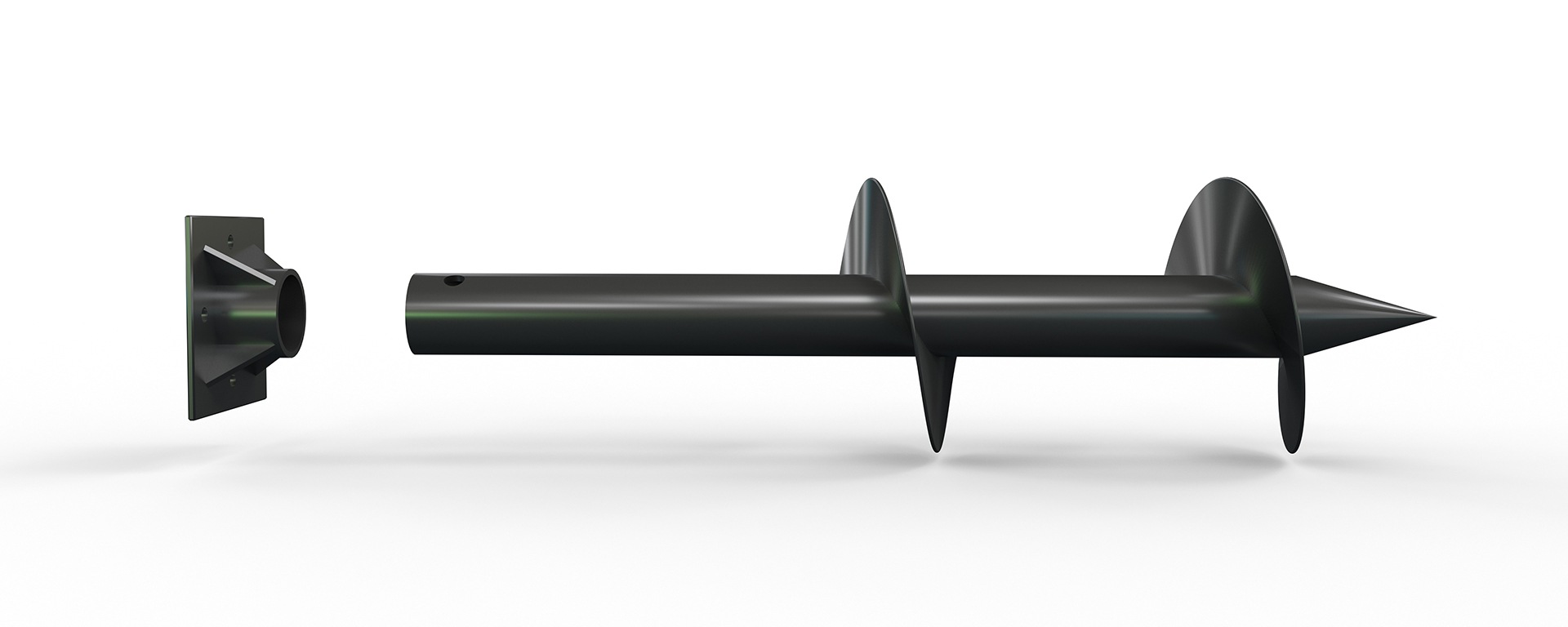

Screw piles, also known as screw anchors, screw foundations, ground screws, helical piles, or helical anchors, which are screwed into the ground, are becoming more popular because they can be installed quickly and are a relatively low-carbon choice.

Image credit: Adobe Stock

New foundation engineering solutions are being developed all the time, such as the Housedeck system, which combines piles with a raft foundation. Another innovative idea is to combine piles with collectors for a ground-source heat pump, in what are called ‘energy piles’.

Building regs

Rules relating to foundations are covered in Part A of the Building Regulations. The first regulations in Part A require that buildings must be constructed so that the combined dead, imposed and wind loads are sustained and transmitted by it to the ground:

(a) safely; and

(b) without causing such deflection or deformation of any part of the building, or such movement of the ground, as will impair the stability of any part of another building.

Also that buildings are constructed so that ground movement caused by:

(a) swelling, shrinkage or freezing of the subsoil; or

(b) land-slip or subsidence (other than subsidence arising from shrinkage), in so far as the risk can be reasonably foreseen, will not impair the stability of any part of the building.

Image credit: Adobe Stock

Various regulations relating to foundations are included in Part A. For example, paragraph 2 gives recommended widths and depths for shallow foundations according to the type of soil you are building on and the total load they are carrying.

Talking of Building Regs, building inspectors usually know the terrain in their local area well, so if you are encountering problems with unstable ground, they can a great source of advice on what foundations have worked for other people on similarly tricky ground.

Sustainability

The concrete (and steel) that foundations are usually made from has a large carbon footprint. A recent report from the National Home Building Council, ‘Building Foundation Solutions – Future Proofing Against Climate Change’, sets out lots of ways good practice in foundation engineering should change to both embrace low-carbon construction and adapt to potential extreme weather causes by climate change.

Image credit: Adobe Stock

The report suggests lots of ways you can reduce the carbon footprint of your foundations, including:

- adopting modern methods of construction

- reducing the load, ie building lighter structures

- alternatives to, and reduction of, concrete/cement, by using for example reduced-carbon concrete, such as Cemex’s Vertua or Hanson Ecocrete, or Ashcrete, or ground-granulated blast-furnace slag (GGBS)

- alternative new, low-carbon options, such as, for example, screw piles or hollow piles rather than solid ones

- making greater use of pre-cast piles, as a relatively low-carbon choice vs traditional trench foundations or piles poured on site

- combining piled foundations with ground-source heating

- reuse of existing foundations: the Institution of Structural Engineers has a great paper on this called A Short Guide to Reusing Foundations

Leap Environmental has a carbon calculator for foundation design called Carbon CREDiT, which will calculate the relative carbon costs for shallow-strip infrastructure vs a piled foundation solution for a site.

There are loads of innovative products and new ways of doing things in the world of foundations, so do some research and talk to your architect and building inspector before you call in Dan the digger man from down the road.