How to deal with mould

What causes mould, how you get rid of it, and how to stop it coming back

Our homes are a haven for pets and houseplants, but they can also be the ideal habitat for other, less welcome guests. Among the potential issues, cold and damp can lead to infestations of mould.

Mould can grow almost anywhere where there’s moisture around the home, including on fabrics and wood. Its presence isn’t always obvious in carpets or on beams, but black mould is usually easy to spot, growing as it does on walls, on window and external door frames, and sometimes on bathroom and kitchen surfaces.

Quite apart from looking awful, mould can be hard to get rid of. It’s usually also a sign of issues like rising damp, poor insulation or water ingress. But most importantly, moulds pose serious health risks to vulnerable people, particularly to children or those with certain respiratory or immune conditions. Here we look at the causes of mould, why it can be dangerous, and how to get rid of it.

What is household mould, and what causes it?

You might not realise it, but the world is teeming with microscopic spores. These spread with ease into our homes and other buildings, where they might remain dormant for anything up to around a year and a half. Often that’s the end of the story, but when they encounter the right conditions, spores quickly develop into fungi, producing mould – or even mushrooms.

Different types of fungi thrive in different conditions. You’ll typically only find mushrooms in a saturated fixer-upper, but some moulds will grow readily in any damp space – even in a home that’s well kept. They’re common around window frames and other cold spots, and can grow in the carpets, walls or furniture in damp and poorly-aired rooms.

This causes several problems. Apart from being gross, mould ruins your decor. Some moulds can lead to more significant structural problems, including dry rot. Moulds are often resistant to simple washing and repainting, quickly reappearing even through fresh decoration. And once growing, moulds produce high concentrations of spores, helping them to spread more readily to other parts of the home.

Fungi don’t thrive in dry conditions, so damp is a prerequisite for mould to grow indoors. While this often comes through condensation in poorly ventilated properties, moulds can also grow around rising damp, or in any other wet patches from things like a leaking pipe or roof.

Where does mould grow?

Moulds can take hold almost anywhere around the home that regularly gets damp. They’re commonly visible on the cold surfaces in humid rooms where water tends to condense. This could be somewhere like a bathroom or kitchen window, but it needn’t be – bedrooms can also be very humid, particularly overnight. Water can also condense anywhere where there’s a thermal bridge to cooler outdoor conditions – such as where there’s a gap in wall or roof insulation.

Moulds are common on plasterwork and brickwork affected by rising damp or other types of water penetration. When growing on a ceiling, they can sometimes be a sign of a slow pipe leak, blocked guttering or a damaged roof.

In homes that are very damp and humid, moulds can take hold in fabrics including carpets and soft furnishing. Moulds can also grow in persistently damp lofts, or below suspended floors that haven’t been ventilated properly, with the risk that this could allow dry rot to form.

Why is mould dangerous?

According to the NHS, living with damp and mould can make people unwell. Not all moulds are toxic, but they often produce allergens and irritants. Nearly all fungi release huge numbers of spores as part of their lifecycle, and in higher concentrations these can cause or exacerbate respiratory problems, and worsen asthma or allergies. Prolonged exposure can affect the immune system, particularly in infants, older people or the immunocompromised.

Two common black moulds – Cladosporium and Alternaria – are linked with severe asthma attacks. A third – Stachybotrys chartarum – is known to produce toxins that cause sick building syndrome, and it may also be associated with acute pulmonary haemorrhage in infants.

The health risks from mould have been brought into sharper focus since 2020, and the tragic death of Awaab Ishak. At the 2022 inquest into Awaab’s death, senior coroner Joanne Kearsley found that the two-year-old died “as a result of a severe respiratory condition caused due to prolonged exposure to mould in his home environment”. Awaab’s family had first reported the mould to their social housing provider three years before his death.

In January 2024, the government announced proposals to force landlords to investigate reports of mould within two weeks. If adopted into law, these will compel repair work to begin within a further week.

Deal with damp first

Water is essential for mould to grow, so any efforts to get rid of mould are doomed to failure unless you also deal with the source of dampness. Condensation, formed on cold surfaces, is often a sign that a home is too cold, humid, or both. You can reduce the problem by making sure the building is properly ventilated, either by opening up windows, setting extractor fans to run faster/for longer, or by installing a more sophisticated ventilation system. You can read more in our guide on how to control humidity and condensation.

Where condensation gathers around window and external door frames, wiping them dry should help prevent mould from forming. After baths or showers, wiping or squeegeeing tiles will help prevent mould in grout or silicone seals. In the kitchen, it’s important to cover pans, and to run extractors when possible.

In general, setting a higher room temperature helps prevent the conditions required for mould. Air can hold more water as it heats up. This lowers its relative humidity (RH), preventing condensation, and ‘making room’ for more water to evaporate.

Another option is to invest in a dehumidifier. “Mould occurs at around 68% RH,” explains Chris Michael, managing director of dehumidifier manufacturers Meaco. “A dehumidifier tasked to reach and maintain a healthy relative humidity of 50% to 55% prevents the damp conditions mould requires.”

When the problem is damp near a ceiling or at the top of walls, you might find the cause by investigating the loft space or roof in the area above. Lost roof or ridge tiles, damaged or blocked gutters or damaged or missing architectural features can all result in water ingress. It can be easy to find leaking pipes in loft spaces, but less so if they’re boxed in. Depending on your level of competence, it might be easier to call in a professional.

The same can be true in cases of rising damp. This is commonly caused where the damp-proof course is bridged, for example if it’s overlapped by plaster or render, but it can also happen where the external ground level is raised, for example by the later addition of planting beds. You can alleviate the issue with DIY silicone injections, but it may be worth paying more for a professional if they’ll back up their work with a long guarantee.

Even after you’ve fixed a damp problem, it takes time for masonry, wood and plasterwork to air out. It may be weeks before a wall is fully dry, and you shouldn’t attempt permanent redecoration until it is.

How do you get rid of mould?

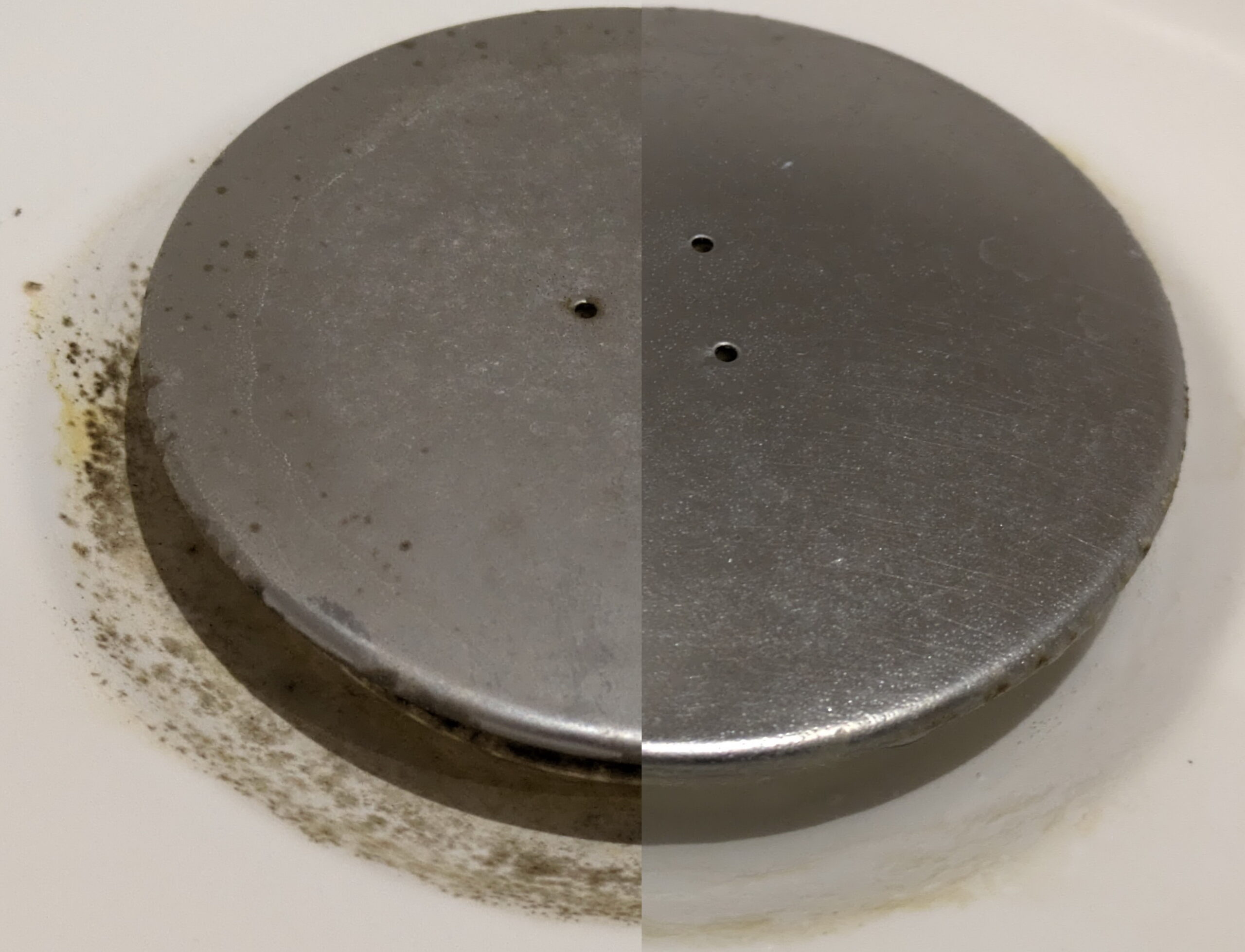

You can kill black mould on a painted wall by spraying it with a mould remover product, or one you’ve made yourself by diluting one part of bleach in 10 parts of water. Bleach sprays can also be effective against mould in grout and silicone sealants, but they may need repeated applications for the best results. On smooth surfaces like tiles, you can also treat mould by wiping it with neat white vinegar.

On porous surfaces, fungal spores can spread further than visible mould, so when treating with bleach it’s wise to spray up to a metre beyond what you can see. You’ll also need to wear hand and face protection, and to mask or protect furniture or carpets that could otherwise be damaged by bleach droplets. Doors should be shut to prevent spores from spreading, but open windows to allow air circulation.

As mould can be very dangerous, if it covers a large area (greater than 1m²), is caused by contaminated water or isn’t black mould (or you’re not sure), it’s best to call a professional.

Before redecorating, it’s vital to make sure you’ve both killed any mould, and dealt with the damp problem that caused it. If not, mould will simply regrow through any fresh paint or papering, or start again if the surface is still getting damp. In areas where it’s hard to completely avoid condensation, using bathroom and kitchen paint will help inhibit regrowth. As a last resort, a damp-sealing paint can prevent penetrating damp from surfacing in problem spots, but this is likely to just shift the trouble elsewhere.

It’s usually impossible to remove mould from wallpaper and non-washable fabrics such as soft furnishings – you may need to replace or re-cover damaged items. Washing is unlikely to restore badly affected fabrics, but you can remove mould from washables using a cycle that heats to at least 60°C.

Where the damage is more severe – for example in properties with extensive water penetration and large areas of mould, it’s best to call in an expert. In these cases it might take significant building or restoration work to dry the property out and prevent mould from returning.

Above all, it’s important to remember that mould and mould spores can be hazardous to your health. You should quickly treat any mould that appears, get rid of any items that can’t be cleaned, and address the damp or condensation that’s creating the right conditions for it to thrive.